A truly great product should first and foremost fulfill a need. Consider the explosion of leisure wear during the pandemic. After a few months of working from home, people were ready to ditch their slacks and pencil skirts.

“If you build it, they will come.”

The old way of thinking assumes that if you create something of high enough quality, the market will magically respond positively. However, design thinking asks who the product or service is for and how they will use it.

What is Design Thinking?

Design thinking is a problem-solving method that recognizes failure as an essential step in the process of developing something new. It’s a user-centered design approach for finding the best solution through creativity and collaboration.

The term “design thinking” wasn’t coined until the 1990s, but creative problem-solving in modern design got its start in the 1960s. MIT’s Buckminster Fuller is credited with developing an organized process for pinpointing design flaws and coming up with solutions. Around the same time in Scandinavia, design-by-doing was gaining momentum, pushing designers to break away from a 2D space and physically test ideas on the fly.

At the end of the 20th century, David Kelley founded a group of designers called IDEO and promoted the idea of “creative confidence,” breaking down the process of design thinking into individual phases. IDEO isn’t an exclusive club. They include professionals from a variety of fields like industrial design, anthropology, and law, with the goal to encourage anyone to use creativity for problem-solving, even if they aren’t in a creative field per se.

Nowadays, user experience (UX) design is based on design thinking principles, playing a key role in the creation process of many products we use daily. From the gamification of language learning on Duolingo and the convenience of a wireless Dyson vacuum, getting into the mindset of users from the get-go leads to product design that feels organic and obvious.

The 5 Design Thinking Phases

It’s important to note that while there is no set definition or strict rules for design thinking, the goal (and order) of each phase is generally agreed upon. Keep in mind that you can always circle back if things aren’t working. In fact, that’s the entire point.

1. Use empathy to understand your customer’s needs.

Before you jump into brainstorming, the first step in design thinking is to talk to the people who will be using the product. Avoid making assumptions about the users’ wants and needs.

Design thinking encourages you to connect with your target audience in both structured and unstructured settings. While the old-school way of doing user research through surveys and focus groups is still useful, it should be used as a springboard to in-depth interactions with the people you are designing for. Some design thinking examples of using empathy to connect with user needs include:

- Inviting participants to share their experiences in an unstructured interview setting.

- Observing authentic user behavior without interference.

- Creating a narrative around the user and product that helps you connect with their current pain points.

It may feel impossible to satisfy everyone’s needs at first, but don’t panic—design thinking asks you to focus on collecting and analyzing data in the first phase. Don’t feel pressure to come up with solutions right away, you’re just getting started.

2. Define the problem that you are trying to solve for the user

Now that you’ve established your customer’s needs, you can focus on solving their common problems. Don’t assume that these issues are obvious. Design thinking pushes you to dig into the “whys” behind these problems.

Let’s say you were asked to design a public park. In the first phase, you collected all sorts of data on what people like and don’t like about their local green space.

- Overcrowding

- Poor drainage

- Lack of lighting

Assessing these problems from a user-centric perspective will give you further insight into any pain points that you may have overlooked or misunderstood, and how they can be addressed. Using a question format, you can start to understand the root of the main issues that kept coming up. Ideally, this leads to thoughtful discussion and invites different perspectives.

Turning the problems into user-centered questions:

Overcrowding: Why are people spending time in only one section of the park?

Poor drainage: Why aren’t children playing in the park after a rainstorm?

Lack of lighting: Why are people nervous to walk through the park at night?

Next, you need to come up with a problem statement that will guide your design process. Keep it short but with all the necessary information (who, what, where/when, and why) to give yourself clear parameters. In this case, the problem statement could be:

The current park’s state of disrepair has led to safety concerns. The residents need an accessible public green space for visitors of all ages, at different times of day, and in all weather conditions.

Now that you’ve got a clear idea of the problem you are trying to solve, you can start to explore solutions.

3. Ideate to come up with as many possibilities as you can

One of the hardest parts of pitching new ideas is staying clear of the status quo. This is why it’s so important to create a safe space for free thinking and collaboration. A brainstorming session can be a great way to generate new suggestions or possibilities, but sitting in a room with colleagues and jotting down words on a whiteboard isn’t the only (or ideal) methodology.

Design thinking teaches us to embrace other ideation techniques to get the creative juices flowing:

Change your environment: Go to your local park at different times during the day or week and see what you notice.

Employ reverse thinking: Instead of asking “How can we make this park as accessible as possible?” Turn it around and ask, “How can we make this park as unaccommodating as possible?” By pretending to thwart your own goals, you’ll highlight obstacles you hadn’t previously considered—and your plan of attack to overcome them will be stronger for it.

Make a list of assumptions, then challenge them: Everyone enjoys a garden full of beautiful flowers, right? But flowers can aggravate some parkgoers’ allergies. A big flower garden also takes up space that kids or dogs could otherwise romp through. So rather than assume a garden smack in the middle of the park is a no-brainer, challenging your own beliefs shows that planting one in a more secluded area is the best solution.

This isn’t a one-time process. Ideating freely means you’re creating fertile ground for creativity and open thinking. Be prepared to come back to this phase again and again after testing out new ideas. Design thinking teaches us that it’s important to ditch the fear of proposing a bad idea. You never know—it could be the springboard to the perfect solution!

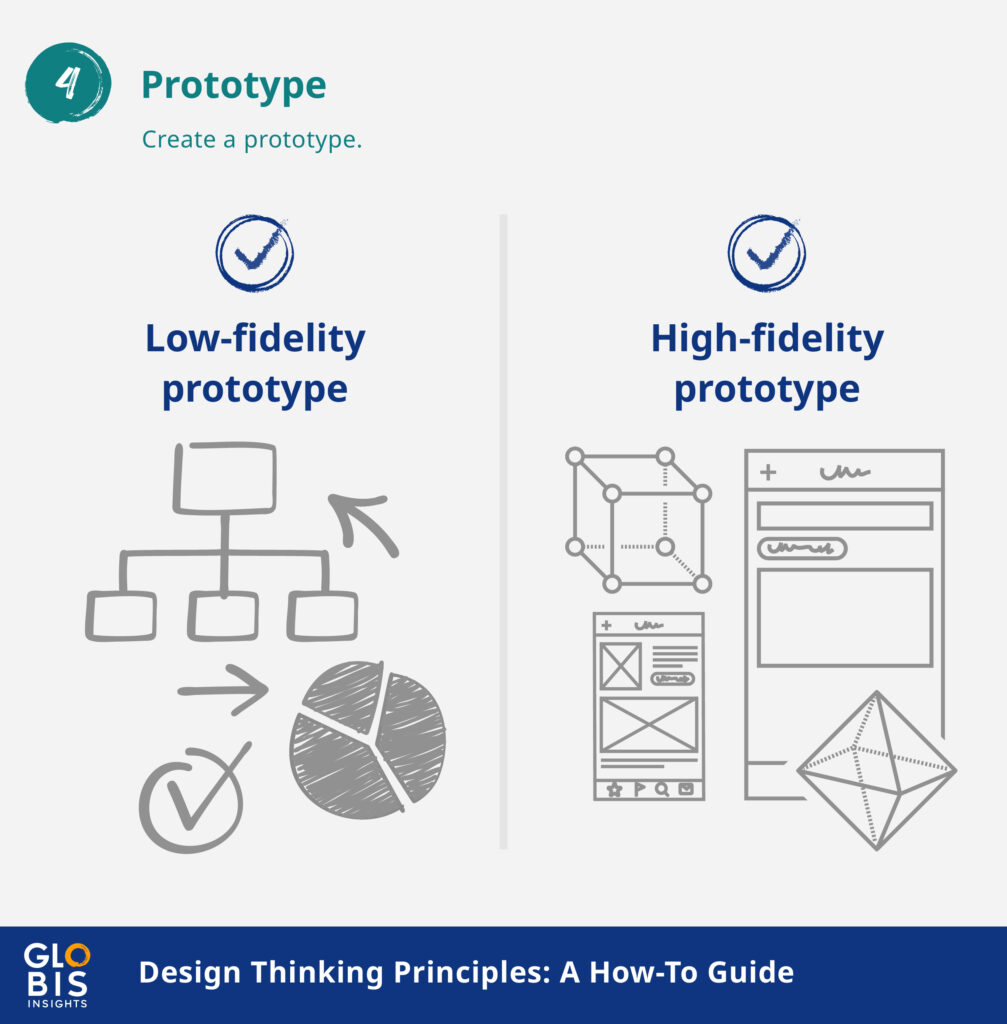

4. Create a prototype

Now that you have your list of user requirements and decided how to best address each one, it’s time to create the prototype. This could mean creating a scaled-down version of a product, a virtual simulation, or mapping it all out on paper.

The point is to allow yourself to fail (cheaply) before investing too much time or money in the real deal. Prototypes don’t have to be fancy or pretty. But depending on the project, they’ll need to be either low-fidelity or high-fidelity prototypes.

Here’s the difference:

Low-fidelity prototype: Anything from a simple storyboard to a collection of materials considered for use in the project. The concern is not strict realism, but to get a feel for the project. Creating a low-fidelity prototype is quick and doesn’t require any specific design expertise, either.

High-fidelity prototype: An accurate representation of the product or project, either scaled down or true to size. It can be created digitally or physically and offers a clear visual representation for stakeholders and users alike. Creating a high-fidelity prototype requires more time, money, and adjustments can’t be made easily.

5. Find flaws through user testing

Design thinking is focused on creating the best possible user experience, so testing plays an important role. Keep in mind that how you go about testing is just as important as who you invite to participate.

When products aren’t tested with a varied enough user base, you can run into situations like facial recognition technology that has lower levels of accuracy for people of color. The consequences of a user testing pool that lacks diversity (age, race, sexual orientation, socio-economic status etc.,) can lead to products that work well, but only for certain people.

For many people, the testing phase of any project is likely to induce fears of failure and criticism. Luckily, design thinking encourages you to break away from the finger-pointing attitudes that can occur in a typical critiquing session.

Being the target of harsh and unconstructive criticism can squash anyone’s creativity. If you’re not sure how to go about offering (or accepting) feedback without demotivating yourself or your team, check out Michelle Lim’s article: Design Thinking Critique: Perils and Pitfalls of “The Crit”

Sometimes the most innovative solutions are forged out of the heaviest restrictions—but keep in mind that nobody will want to share their next great idea if they’re going to be ridiculed as a result.

What are the benefits of design thinking in the workplace?

Despite the name, design thinking is not solely applied to product development. It’s a non-linear problem-solving method that’s practical for everyone—regardless of their job description.

These design thinking tools can benefit anyone in any workplace:

Tap into your creative confidence.

The benefits of creativity aren’t reserved for artistic fields. As humans, our ability to think outside the box is an incredible skill, and it needs to be consistently nurtured. Creative confidence is simply finding the creative spirit that you were born with, and then harnessing it to come up with new ideas. When you approach your problems with creative confidence, you’ll be empowered to let go of the less-than-stellar ideas and embrace the gems along the way, too.

Problem-solving with empathy

AI’s rapidly expanding applications in the workplace can make it easy to fall into a doom spiral of worry that we’ll soon all be replaced by machines. Design learning (and thinking) offers a key skill set that is still (and will hopefully remain) in the blind spot of our binary brethren at arms: empathy.

Tom Kelley, cofounder and chairman of the venture capital firm D4V (Design for Ventures), and partner at design firm IDEO, insists that empathy gives startups a competitive edge.

“Most of my clients are very, very good at problem-solving,” he says. “But you’ve got to know what problem to solve. If you take the empathy of design thinking and use it all the time, you will spot the problem that others aren’t trying to solve yet.”

Experimenting and pivoting

Nobody likes to fail, but if you experiment enough and pivot in the right direction, failure leads to success. From Corn Flakes to the discovery of penicillin, there have been more than a few discoveries born out of failure.

Finding your creative confidence will help you get comfortable pitching new ideas without worrying about knee-jerk reactions from your peers. You’ll be coming up with fresh ideas, and embracing the resilience to try, adjust, and try again.