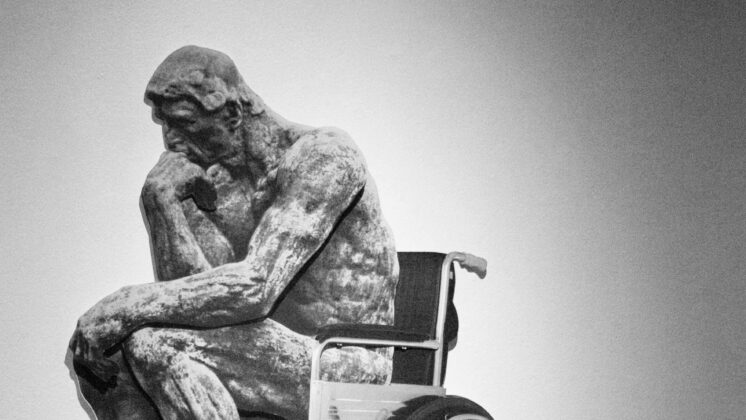

Rodin’s powerful Thinker, a muscular man with his hand curled under his chin, sits—unusually—in a wheelchair. He is deep in thought.

The original Thinker was a symbol of the values of philosophy and poetry. This one says something different—Is philosophizing a disability? The image suggests that people lost in thought move through life in a fundamentally different way. Walking versus wheeling.

The wheelchair forces a complete re-evaluation of Rodin’s iconic sculpture. As an exercise to help viewers think again, Nakrob Moonmanas’s work is invaluable.

Businesspeople make critical decisions every day, all of which are influenced by their perspectives. In a world where news outlets and interest groups sometimes push biased narratives, the ability to see alternative interpretations and perspectives is critical for businesspeople. This is a skill that can be practiced through art.

The classic narrative isn’t always true.

Moonmanas collages Thai and Western art together using simple editing software, but his art is anything but simple. “Combining many things from such different times and spaces represents contemporary ideology—we live in a collage world within a collage universe,” he says. Through his work, he tries to encourage alternative narrations and interpretations. He wants to challenge existing narratives—What is ‘Thai?’ What is ‘sacred?’ What is ‘sacrifice?’—and in doing so, encourage critical thinking.

This focus on narrative makes sense when you understand his childhood. Moonmanas was born and raised in Bangkok, which was “full of both beautiful and ugly things.” When he was small, he rarely thought about being an artist because “Thai society encourages children to walk more honorable or stable paths,” Moonmanas explains. The path of an artist was neither of those things.

The narrative that art wasn’t honorable stung, but he couldn’t ignore the call of creativity, and started as a graphic designer in a Bagnkok fashion house. He worked with big-name clients including Thai Airways, Mercedes Benz, One Bangkok, and Vogue Thailand. But the Thai fast fashion industry didn’t fit well with his own philosophy. If his work helped an industry that regularly exploited working-class communities and harmed the planet, was his job truly “honorable?”

His job might be stable, but it didn’t feel right. He decided to forge his own path, and became a full-time visual artist and illustrator in 2014.

Alternative interpretations make for better decisions.

Being able to see different interpretations is a key skill in any line of work, and business is no exception. Consulting agency McKinsey promotes six problem-solving mindsets for uncertain times, one of them is the dragonfly-eye. Just as a dragonfly sees the world from 360 degrees of perception, it is important to perceive a problem from multiple lenses in order to solve it. Other research shows that multiple perspectives help decision-makers make better-informed choices.

Moonmanas’ work challenging classical interpretations of ‘Thai-ness’ faced negative feedback from specific conservative groups concerned about the use of religious imagery, or photographs of His Majesty the King Bhumibol Adulyadej. He accepted the criticism with grace. They are, after all, just another alternative narrative or interpretation of his own work. “It’s fine that some people do not like my work. We have our own freedom to express our own opinions, and of course, we all have freedom to interpret art.”

Accepting the value of other perspectives, even ones you disagree with, is the starting point for identifying novel threats or opportunities. In business, this means talking to all stakeholders of a given venture, or going through the customer journey yourself in order to get a wider perspective. And even if you don’t immediately find your solution, teams with a greater variety of perspectives are smarter and make more money.

Seeing different narratives takes practice.

Being able to see alternative narratives takes practice, and just imagining being in someone else’s shoes doesn’t cut it. You’ve got to talk with diverse people, put yourself in new situations, expose yourself to art. Even Moonmanas, whose art shows him to be a master of seeing things in a new light, is always looking for a new perspective. In 2020, he was accepted to a residency program at Cité International des arts in Paris. He is currently based there. The richness of art, history, and the French contemporary scene is a fresh source of inspiration.

And Moonmanas is not the only one who got to practice seeing alternative narratives in 2020—COVID-19 challenged nearly all businesses worldwide to change, or to fail. It has also forced governments to try unconventional solutions simply to keep their people alive. The ability to weigh multiple perspectives and interpretations in order to make a decision was a matter, in many cases, of survival. Moonmanas, too, is finding new perspectives under this COVID-19 crisis. “It was a significant time for me to connect and reconnect with myself. I tried to stay hopeful by doing artwork.”

Moving beyond coronavirus, the need for innovative problem solvers won’t go away. In fact, as businesses continue to chase after the UN’s sustainable business goals, it will likely increase.

In the meantime, Moonmanas’ work is opening new perspectives and discussion in Thai society. Despite the way he has interrupted the discourse in Thai society and his selection by the European Union in Thailand to create an exhibit titled “The Art of human Rights,” Moonmanas denies he is a star. “I’m a man who tries to express his own narrative. At first I just wanted to do what I loved, just for myself. But I’m lucky enough that other people like my work, too.”