On March 9, after many years of talks and countermeasures involving the British government, the EU, existing steelmakers, and potential buyers, Chinese steel giant Jingye Group announced the takeover of British Steel Limited. It was the second time in four years that the company changed hands.

There had been whispers of a potential sale for more than a year. Attracting any buyer for the perennial loss-maker was tough. Only two came forward: one Chinese, one Turkish.

Why was British Steel so unattractive to potential investors?

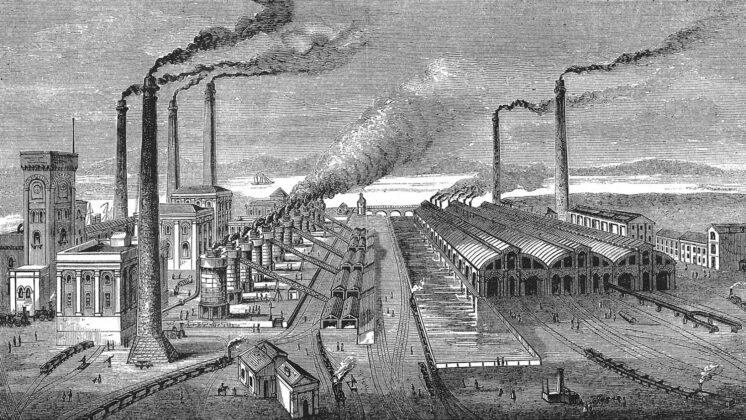

An Uncertain Future from a Glorious Past

The United Kingdom is famous the world over as the cradle of the First Industrial Revolution. Eighteenth-century innovations in a variety of industries—textiles, ironmaking, and machine making—were aided by steam power and a logistical infrastructure on canals, then railways. Things really kicked off in 1855 when Henry Bessemer patented a process to create steel more cheaply than ever before.

In 1967, the British government nationalized fourteen steel producers to form the original British Steel. Eventually, in 1988, that company was privatized and listed on the FTSE 100. When it merged with Dutch steelmaker Koninklijke Hoogovens to form Corus in 1999, it signalled the end of fully British-produced steel.

Consolidation deepened as Tata Steel (part of an Indian conglomerate) then acquired Corus. It was only when Tata sold its long products division in 2016 to London-based investment firm Greybull Capital (for the princely sum of £1) that the British Steel name was revived and back in British hands.

Steel has epitomized national pride. Many hoped for British Steel to stay British.

It is hard to deny the importance of steel. After all, it’s used in cars, construction, household appliances, aerospace, defense, and infrastructure, among other things. At its peak in 1971, the UK steel industry employed 320,000 people.

But as productivity improved, fewer workers were needed. Further, the importance of steel produced in the UK diminished not only at home, but globally. In 2018, the UK was only the world’s 22nd-biggest producer.

Despite the UK’s convenient shipping ports and proximity to the European trading bloc, the prognosis for its steel is hardly looking bright.

According to a briefing paper from the House of Commons Library published in 2018, “[a]utumn 2015 saw a crisis in the UK steel industry with the closure or reduction in capacity at major plants.”

Economic output in 2016 was £1.6 billion—0.1% of the UK economy and 0.7% of total manufacturing output. The industry employed 32,000 people—also 0.1% of the total.

Shifting Demand

As students and experts in business strategy, marketing, or economics know, industries rise and fall to match demand. Demand refers to two things: the ability to buy something and the willingness to pay for it. Economists would say that if steel were important enough to the British economy, it would be bigger. Customers either don’t demand it, or they can find a better, cheaper, or more readily available source elsewhere.

Both seem to be the case.

While the UK economy grew 68% between 1990 and 2015 (fueled mainly by growth in the service sector), steel fell more than 40%. In 2016, the UK produced 8 million metric tons of steel. China produced 808 million metric tons (half the world’s total), followed by Japan’s 105, India’s 95, and the US’s 78. Even within Europe, the UK lagged six other countries: Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Poland, and Belgium.

The balance of trade in steel was bleaker still. In 2015, while the country exported slightly more steel than it imported (6.3 million metric tons compared to 6.2), the value of that steel was in deficit (£5.2 billion to buy and £4.8 billion to export).

Who’s taking the lead in steel?

No surprise: China.

Steelmakers often cite the penetration pricing of Chinese companies as a key factor that hurts profit. In 2016, the EU imposed strict tariffs on Chinese steel for this very reason. However, while fierce international competition is certainly a factor, there were a number of others: extremely high prices for industrial electricity (50% higher in the UK than other major EU economies) and the hit the pound took with Brexit, to name a couple.

The Jingye announcement hardly made the news amidst the global coronavirus pandemic, but if people had been watching, they would’ve seen it wasn’t all bad. While the company will lay off around 450 workers, it also promised to save 3,000 jobs.

What the Future Holds

What attracted Jingye to British Steel in the first place?

British Steel complements Jingye because it specializes in long products used in construction and rail. These infrastructure products are essential, allowing Jingye to acquire new IP and new markets—including Europe. Although the UK has decided to leave the bloc, British Steel has an operation in France. Jingye can import raw steel to its plants in the UK and France, add the finishing touches, and circumvent tariffs.

Given all that’s happened over the last ten to twenty years, many might say that British Steel was lucky to survive. Now that coronavirus is raising new questions about business models, what’s in store for steel?

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the risks of overly centralized supply chains. Post-corona, a presence in different parts of the world will become more critical than ever.

Once the current crisis is over, governments will be looking to kickstart their economies and bring people back into the workforce. Infrastructure investment is a good candidate for this, as it creates jobs directly and indirectly, often spilling over into other economic opportunities.

By then, it won’t matter who owns British Steel—only that they’re helping the economy get back on its feet.